In Conversation: Grant Allen, Co-Founder of Cemento.

Grant Allen, co-owner of Cemento, partnered with design firm Basha-Franklin to craft a bold and immersive feature wall for the staircase at Myo St Paul’s.

Rising through the heart of the space, the staircase seamlessly connects all three levels, fostering interaction and movement among Myo’s members. Rooted in innovation and evolution, the design blends rich textures, vibrant colours, and sustainable materials to create a dynamic, multi-sensory experience.

Grant also sits down with us and delves into his design journey thus far and tells all about the future of Cemento.

Words: Grant Allen

Photography: Taran Wilkhu

Short-Film: Jack Wells.

Originally, I wanted to be an architect – though, timing-wise, it was probably the worst possible moment because the industry was struggling and loads of architects were out of work. So, after a rethink, I ended up shifting to industrial design.

I studied industrial design and was keen to get into cruiser boat design. I went for this brilliant interview with Yacht Designer extraordinaire - Tony Castro – which was a dream opportunity, but I didn’t land the job. Turns out I didn’t know enough about furniture design and interiors at the time - hugely frustrating.

So, I thought right - let’s fix that, and I started searching for furniture design roles. That’s when I came across a joinery company called Dealerward. I joined them to build up my design skills, especially in furniture, and ended up staying for 10 years. I eventually became their Design Director and a shareholder too. I never did make it into boat design in the end – but that’s really where my love for interiors and furniture design properly took off.

Definitely, I’m severely dyslexic, but I’ve always loved problem solving and figuring out how things are made. I was that kid constantly taking stuff apart, and not always putting it back together properly… but eventually I got the hang of it.

For me, one of the ultimate design challenges is a building. Some people are obsessed with cars or tech – but I’ve always been fascinated by the spaces we live in. I grew up in Guernsey, a tiny island with not much of a design scene outside of architecture. That’s where the interest started – it just made sense for the way my brain works, a natural fit for someone who was more design-engineering minded.

Technology has completely changed the game, especially in manufacturing. What used to take 12 weeks is now being turned around in six, sometimes less. Speed, precision, automation – it’s all moved on massively.

Beyond the tech though, one of the biggest shifts has been in attitude towards purposeful design. What started off as a bit of a trend – keeping things natural, raw, honest – that’s not just a style anymore, it’s the baseline.

Honest design has really taken root. It’s less about gloss and more about the purpose, materials, and making things that actually feel good to live with and are more meaningful, especially post-Covid. I think that whole period made people stop and think about how their spaces affect their wellbeing. Suddenly it wasn’t just about what looks good – it was how it feels, what it’s made from, how it impacts our health. For the first time, we were all aware of what we were touching, breathing, standing near. Even that simple visual of the 2-metre distance – it made you see space differently.

For me personally, it was a real wake-up call. It made me far more conscious of what I’m surrounded by, and I think that’s shifted our approach to design across the board.

It might sound a bit corny – but honestly, I just wanted to make cool stuff out of concrete. I was totally obsessed with the material. Coming from a furniture background, concrete was always one of those materials that felt full of potential but was just frustrating to work with. Back in my joinery days, we worked with a concrete supplier who had a stream of issues. I remember thinking, why can’t they get it right? That frustration turned into curiosity, then a mission to find out who was doing it better.

The US and Australia were streets ahead. They were really pushing what concrete could do. Whereas in the UK, it felt like no one was really taking advantage of the material or the technology behind it. For a material that had been around thousands of years, it felt crazy that the UK market was so behind.

The material gets a bad rep because of the carbon footprint – and fair enough, some of that is justified. But there’s been massive progress. The fact that you can now reuse it, recycle it, reduce the footprint – for me, that’s where the opportunity is. I genuinely believe concrete has the potential to help solve some big sustainability problems. Structurally, it’s solid, and if we treat it properly, it should never end up in landfill – it can be repurposed again and again.

So really, it all came from that love for the material and wanting to do something different with it. I ended up finding this company in Italy who were spraying concrete using limestone waste – a completely different approach – and I just thought, this doesn’t exist in the UK. That was the light-bulb moment. I wanted to take all those global influences, the tech, the attitude, and bring it here. That was the big driver behind starting Cemento.

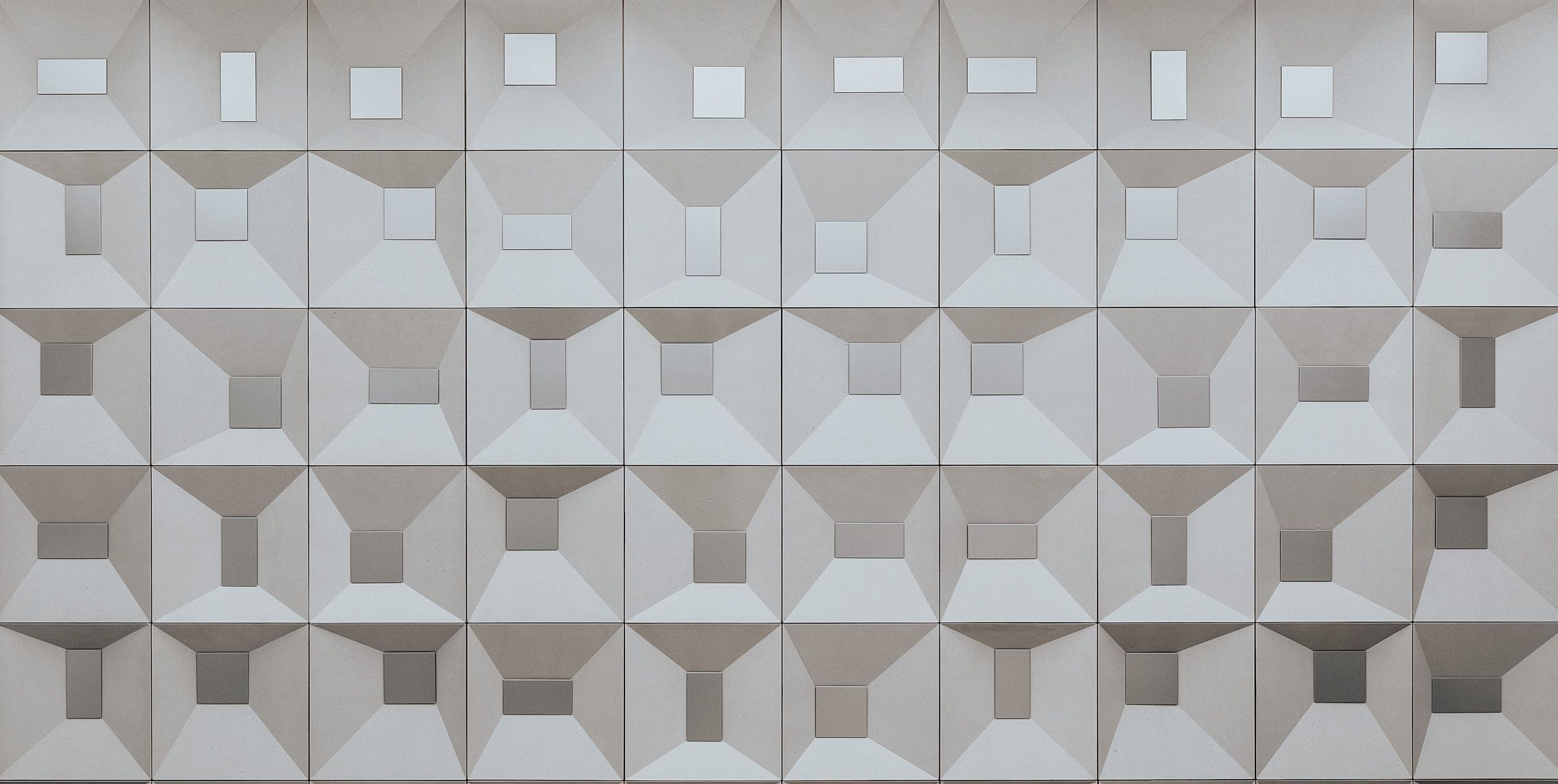

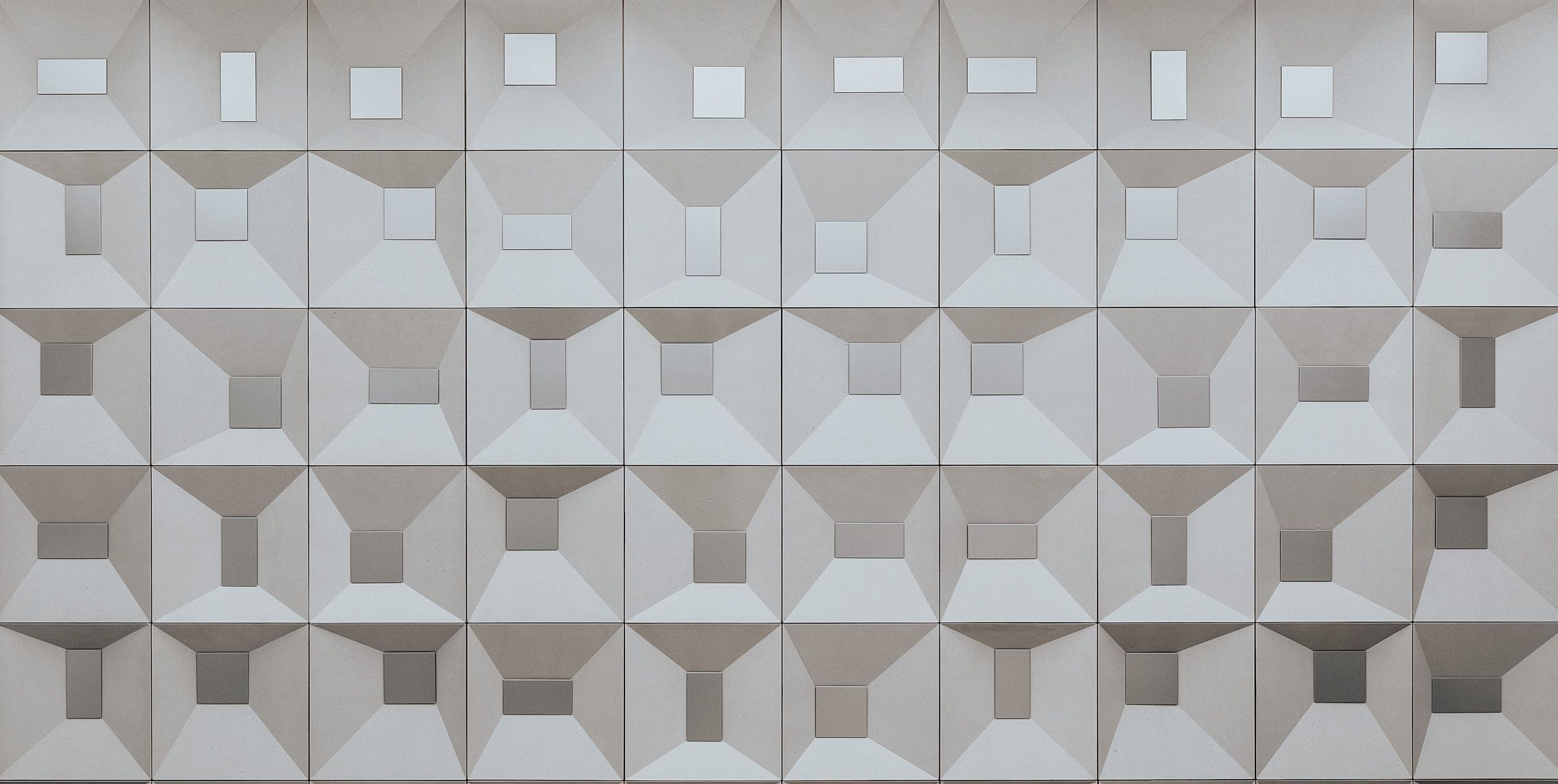

Our surface is usually flat and Basha-Franklin challenged us to make this 3 dimensional. Presenting a really strong concept, it was our job to figure out how to bring it to life—especially all those faceted sides. That’s where things got exciting.

We started with sketches, then mock-ups, all key to align everyone’s expectations and achieving client approvals. It had to look good—be modular, easy to install, and ideally, reusable/demountable. That kind of life-cycle thinking is something we try to embed in everything we do.

What I love most is that initial problem-solving stage. It can be frustrating at first, but that’s what drives you. And when you manage to not only solve the challenge but surprise your client? That’s the real reward. Working with the Basha-Franklin team was a joy, and seeing the idea come to life—especially something that size (12 meters high) —was a proud moment for the whole team.

When people ask me what I do, I often say, "I’m a problem solver." That’s how I approach design. Say a client wants a strange, sculptural object suspended from the ceiling, looking like it’s floating—can we make that happen? That’s the joy for me. It’s in the figuring out, the experimenting, and then seeing it come to life.

In such a fast-paced industry, it’s especially rewarding to see those ideas become real, and to see them fairly quickly. That moment when the design becomes tangible—it never gets old.

It’s definitely a challenge being a designer-maker in today’s world. I’ve been fortunate to work within small teams and have support around me, but that’s not always the case for everyone. The idea of the lone craftsman—someone who can design, make, run a business, and find clients—is becoming harder and harder to sustain, especially when you’re competing with much larger organisations.

Doing things sustainably as a small business is especially tough. We’ve always taken the approach of embedding sustainability into how we work, rather than just chasing certifications. Over the years we have lost projects not having an EPD for example. It’s a long, expensive process—you can’t even start it until the product’s been in the market for 18 months. But we wanted to approach it properly: reducing energy use from the start and making sure the materials we used made sense. I’m pleased to say we now have EPDs for all our main ranges.

A lot of smaller studios just can’t afford to go through those kinds of processes, even if they’re doing the right thing. And without those certifications, they’re often locked out of the bigger projects, which is an issue.

I think the industry could do more to level the playing field—whether that’s simplifying the regulatory side or offering financial support to help small companies meet those benchmarks. There’s a huge benefit to working with smaller studios—we’re flexible, quick to adapt, and we often bring fresh, thoughtful approaches to design challenges.

The industry would have a richer diversity of choice if SME’s were given more visibility and opportunity to contribute to innovative solutions.

The first thing that comes to mind—and it might sound simple—is that they’re just genuinely great people to work with. And that really does matter. The team you collaborate with has such a big impact on the project experience, and with Basha-Franklin, there was a real sense of passion that came through in everything they did.

At first, I thought what stood out was their strong interest in natural and raw materials, and their appreciation for the honesty and character of those materials. But after the project, when I had a bit of time to reflect, I realised it went deeper than that. What really made them unique was their genuine interest in the process behind the materials—not just what things look like, but how they’re made.

These days, in a world where so much is done remotely—over Zoom or via emails—it’s becoming rare for designers to visit workshops or want to be hands-on with the process. Basha-Franklin was present and involved at key moments in the process which was really refreshing. They recognised when something important was happening and took the time to come into the workshop, see how things were taking shape, and understand how we work. It made the collaboration feel more connected and thoughtful. Honestly, that kind of involvement is becoming less common, so when it does happen, it really stands out. It reminded our team how valuable direct interaction is—not just for the design process, but for building trust and creating something truly considered.

Talking about sustainability can be a bit tricky, to be honest—not because we’re not committed, but because it’s never been a buzzword or a trend for us. It’s just always been part of how we work. From day one, our whole process has been built around using mineral waste—mainly limestone and marble—to create something useful and beautiful. So, sustainability isn’t something we bolted on later, it’s in the DNA of what we do.

It’s not a tick-box exercise—It’s something we talk about regularly, usually as part of our monthly team check-ins. It’s not always about big, headline-grabbing changes either. Sometimes it’s the small, consistent things that make the biggest difference.

For example, our workshop is powered by a solar array on the roof that supplies 90% of our energy. That’s a practical, straightforward step—but one that means we’re not just talking about reducing our footprint, we’re doing it every day.

We also think a lot about the full life-cycle of the product. It’s not just about making something from waste—it’s about making sure it can be taken apart, reused, and re-imagined again in the future. That circularity is super important to us. We want to create materials that have more than one life and that can be reinvented into something new.

We’ve been doing this for over 10 years now, and along the way we’ve ticked off a lot of the certifications the industry asks for. But truthfully, that’s not the end goal. For us, sustainability is about asking the right questions every day: Are we reducing energy? Are we designing responsibly? Can this material go on to have a second or third life?

It’s less about getting a stamp of approval, and more about knowing we’re building something meaningful—with as little waste and as much care as possible.

The response has been really positive—from the client right through to our own team. One of the comments that stuck with me was from someone at MYO who said, "It looks much better than I was expecting!" Which might sound like a backhanded compliment—but actually, it’s the opposite. It was such a unique installation that I think not everyone fully grasped what Basha-Franklin had envisioned until it was in place. That element of surprise is a sign of its success—it exceeded expectations and helped people really connect with the space.

From a marketing perspective, it's been a standout piece. We’ve used images of the wall in presentations to new clients, and without fail, it sparks curiosity. We always get questions like, "How did you install it?" "How is it fixed?" "What’s causing that beautiful light refraction?" And when people are asking those kinds of questions, you know it’s made an impact—it’s inviting people to look closer.

But honestly, one of the most rewarding parts for me was seeing how much our internal team enjoyed working on it. From the workshop to management, and especially the installers on site—everyone was engaged. People were asking questions, sharing progress, and I even saw installers taking photos to show their families. That’s when I know a project has really landed—when there’s a sense of pride and excitement at every level of the process.

This one was original, it was different, and it brought people together—from design to delivery. That, for me, is what makes it truly successful.

The dream—the ultimate goal—has always been to take something old and overlooked and give it a completely new life. For me, that means using the waste from an existing building and transforming it into something meaningful for the very same space. Obviously, we’re not in the business of constructing entire buildings from scratch, but we can take parts of them—say, an old stone floor that’s no longer needed—and reincarnate that material into something like public furniture for the new development.

That circularity, where waste from a site is reused on the same site, is a powerful idea. It’s not just sustainable—it’s poetic. There’s something really satisfying about that kind of full-circle thinking. And long term, that’s where we want to be as a company: nothing to landfill, and everything we make designed to be broken down, reused, and re-imagined again in the future.

We're taking a small but exciting step in that direction right now with a project for a large University campus. It’s an old 1970's building being partially demolished, and we’re taking some of the sandstone waste from that demolition, grinding it up, and turning it into wayfinding totems for the new campus. It’s a modest intervention, but it’s a start.

One idea I’ve always loved is creating street furniture through community involvement. I imagine using demolition waste from a local site to pour something like a bench or planter, but having the community actually help make it. If we design the moulds in a way that’s safe and accessible, suddenly it’s not just about sustainability—it’s about social engagement too. You’ve got people sitting on a bench they helped create from the bones of a building they once walked past every day.

That, to me, is where Cemento could really go next. It might take five years, it might take ten—but we’re making those small steps. And each project, like those wayfinding totems, gets us a bit closer to that bigger ambition.

We’ve got a lot of exciting things happening in the short term. One of the biggest changes is that we’re moving into a new workshop later this year—doubling the size of our current space. That means more room to experiment, more capacity, and some new toys (well, tools) to play with on the technology side. It’s going to open up a lot of possibilities for how we work and what we can make.

Product-wise, we’ve just come off the back of a really positive response at the Surface Design Show in February, where we launched a new direction—more cast-based applications of the material. One example is Formella, which moves away from flat panels into more sculptural 3D tiles. What’s exciting about it is how adjustable it is—it’s not just one finish or colour, it’s something that can evolve with a project. It can be developed hand-in-hand with designers, and that kind of collaboration is something we’re really leaning into.

After 10 years, there’s a growing confidence in the material because it’s been tried, tested, and trusted across so many different applications. That gives us a solid base to start pushing further—releasing things we’ve been sitting on for a while, exploring new forms, and saying yes to a bit more risk.

One thing we’ve realised is how much more we want to be involved in the early design stages—to support designers more closely, almost on a day-to-day level. We’re a small, agile team, so if a project comes along that needs R&D or a totally custom solution, we can jump in and make it happen.

And perhaps most excitingly... colour! There's going to be an explosion of colour in the work we’re doing moving forward. It’s something we’re really embracing—not just as a visual element, but as a way to bring more joy and identity to the projects we’re involved in.

So yes, big physical changes, new products, deeper collaborations, and a bright, colourful future ahead for Cemento. And as always, we’re open to conversations—because some of the best ideas have come from someone just asking, "What if we tried this?"